Our history

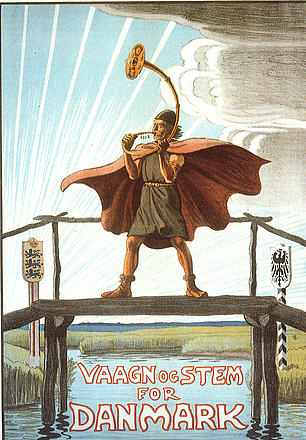

South Schleswig was part of the Danish kingdom for centuries. After the second Schleswigian war in 1864, South- and North Schleswig became a province in the kingdom of Prussia and later the German empire.

After World War I – in 1920 – the region’s people decided in a referendum that North-Schleswig - Sønderjylland – should become Danish again. However, south of the new border the majority voted for Germany. This left a national minority on both sides of the border, and the Danes south of it and established its own schools, church, cultural organisations.

During the years of the Nazi-regime 1933-1945, the Danish minority was officially acknowledged. Nevertheless, local Nazi-authorities often discriminated those who openly displayed their support for Demark. Furthermore, most of the younger men – who were German citizens – were drafted and had to go to war for the Nazi aggressions throughout Europe. Parts of the minority at that time actively got involved in the local resistance movement.

Danish became trendy in post-war-Germany

Immediate after the German defeat in World War II a larger part of the population in South Schleswig thought it achievable and desirable for the German-Danish border to be re-drawn. Not only those who were Danish-minded and had their roots in the minority, but also many who had until then been German-minded were fed up with what Germany had brought them.

The Danish government however foresaw that a revision of the border would leave Denmark with a German minority of a considerable size, and rejected that notion.

Though many Germans suddenly became conscious of their Danish roots and were keen to become Danes. Even if they had to be Danes in Germany.

The large number of refugees from East Prussia, whom in the post-war-years doubled the population in Schleswig-Holstein, furthered the trend.

The native inhabitants, who were often forced to share their houses or apartments with the refugees considered themselves having more in common with the Danes than with the refugees.

The explosive expansion of the minority deflated again as Germany returned to normality. However, the minority was strengthened – compared to the pre-war times. New schools had been founded and the Danish-minded had won quite a few seats in city- or county-councils.

Occasionally this fostered a rather tense relationship between majority and minority.

Political however things became less tense. In 1955, the Danish government and the German jointly signed unilateral but identical declarations about the protection of the minorities. A treaty was unthinkable at that time, as both countries were rather political sensitive both recently having experienced foreign occupation.

The declarations are known as the “Bonn-Copenhagen Declarations”. They amongst other guarantee, that exams from a Danish school in Germany and vice versa are recognised and give access to high schools, universities and other educational institutions in both countries.

Furthermore, they pointed out, that one is part of the minority if one decides to do so. No authority can discriminate against wanting to join any of the two minorities.

Minority policy of today

During the seventies and eighties German society more and more adopted the idea, that it had a certain obligation to contribute to the Danish institutions in South Schleswig. After all the Danish-minded payed income taxes and VAT like any other German citizen.

In the eighties Germany decided to pay the Danish schools the same amount per student as the public German schools receive.

Equality has since then become more common although local authorities might have rather different ideas on how much financial support Danish healthcare or culture should be entitled to.

Since the 1990’ies the minority and not least, its political party - the SSW - has made progress. For decades, the party had only one seat in the Schleswig-Holstenian parliament. Now three or even four is quite common. From 2012 -2017, it was even part of the government in Schleswig-Holstein – one of 16 states that the Federal Republic of Germany consists of.

For decades – if not centuries – the relationship between Danish and Germans, between majority and minority has been characterised by antagonism, conflicts and to some extend even violent conflicts / war.

Today the Germans no longer consider the Danish minority as something odd, but rather as a part of Germany’s and their own history / cultural heritage.

Today there is a cross-border labor market, and the minorities on both sides are not only accepted, but even respected as an important link between two countries and two nationalities.